Life throws decisions at us every day, from choosing what to eat to making major career moves. Most of us rely on gut feelings or what sounds right, but what if you could make better choices by thinking like a scientist?

Think like a scientist: critical thinking for everyday life isn’t about lab coats and test tubes. It’s about using proven methods to cut through confusion, spot bad information, and make decisions you won’t regret later.

This guide is for anyone tired of second-guessing themselves or falling for misleading claims. Whether you’re a student, parent, professional, or just someone who wants to think more clearly, these skills will help you navigate everything from social media debates to major life choices.

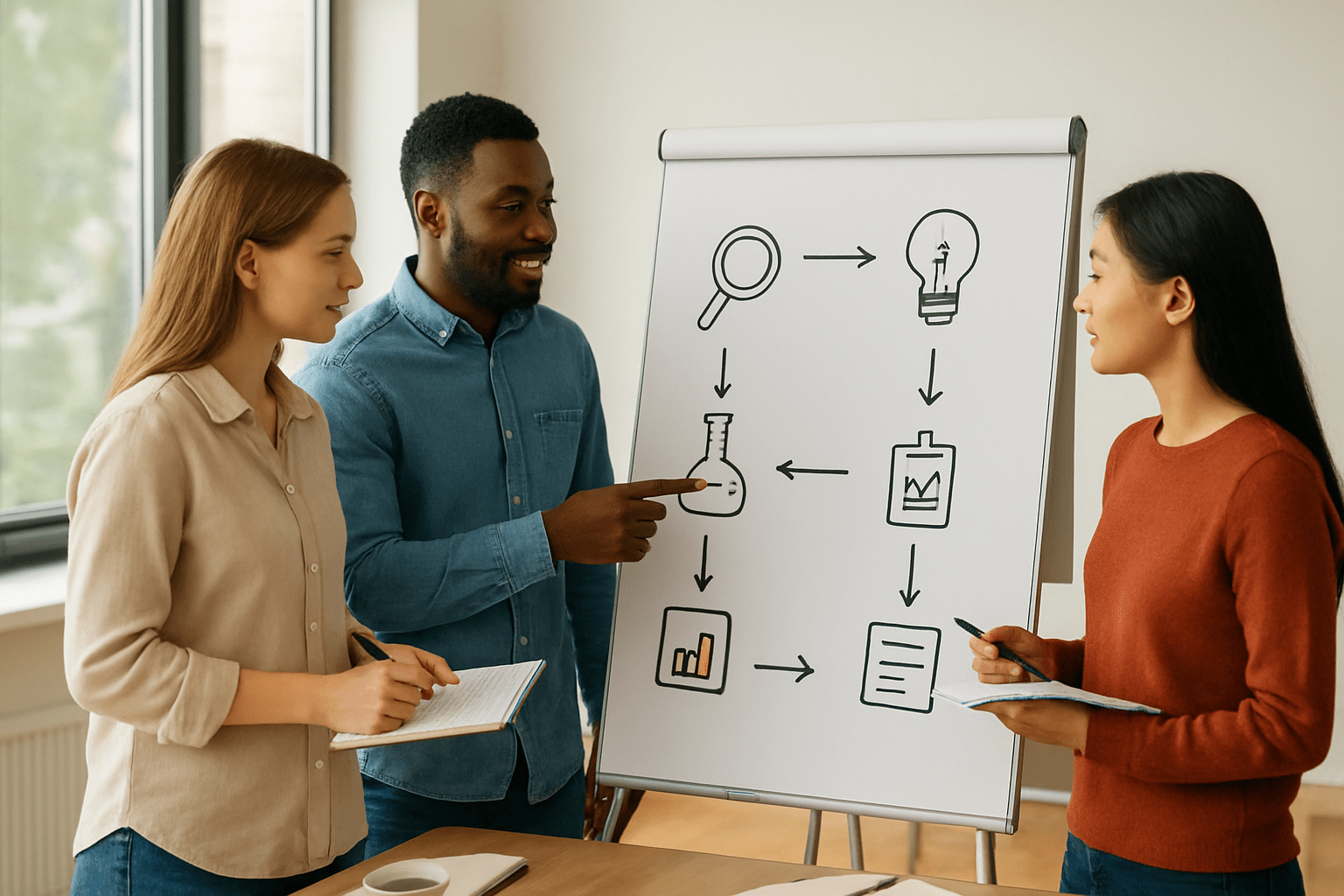

You’ll learn how to master the scientific method for daily decisions by asking the right questions and testing your assumptions before jumping to conclusions. We’ll also explore how to identify and overcome common thinking traps that trick even smart people into making poor choices. Finally, you’ll discover how to develop evidence-based problem solving skills that help you separate facts from fiction and find solutions that actually work.

Ready to upgrade your decision-making toolkit? Let’s dig in.

Master the Scientific Method for Daily Decisions

Ask Better Questions to Uncover Root Causes

Most people jump straight to finding solutions without understanding what they’re actually solving. Scientists know the secret: the quality of your answer depends entirely on the quality of your question. Instead of asking “Why is my teenager so moody?” try “What specific situations trigger my teenager’s mood changes?” The first question leads to assumptions and generalizations. The second opens up real investigation.

The best questions dig deeper using the “Five Whys” technique. Your car won’t start. Why? The battery is dead. Why? The alternator isn’t charging it. Why? The belt is loose. Why? It wasn’t properly tightened during the last service. Why? The mechanic was rushing. Now you’ve moved from “dead battery” to “need a new mechanic.”

Transform vague problems into specific, measurable questions. Replace “How can I be happier?” with “What activities in my daily routine consistently improve my mood for at least two hours afterward?” This shift makes problems solvable rather than overwhelming.

Form Testable Hypotheses Before Jumping to Conclusions

Your brain loves creating instant explanations, but scientists pause to form testable hypotheses first. When your coworker seems distant, resist the urge to conclude they’re angry at you. Instead, create multiple hypotheses: they’re stressed about a deadline, dealing with personal issues, or maybe they’re just having an off day.

A good hypothesis makes predictions you can test. “If my coworker is stressed about the quarterly report, they’ll seem more relaxed after the deadline passes.” “If they’re upset with me, they’ll avoid eye contact during our next team meeting.” “If they’re dealing with something personal, they’ll be distant with everyone, not just me.”

Make your hypotheses specific and time-bound. Instead of “Exercise will make me feel better,” try “If I walk for 20 minutes every morning this week, I’ll report higher energy levels on my daily mood tracker by Friday.” This gives you clear criteria for success or failure.

Gather Evidence Systematically from Multiple Sources

Scientists never rely on a single data point, and neither should you. When making important decisions, collect information like you’re building a case. Your friend recommends a restaurant? Great, that’s one data point. Check online reviews, look at the menu, drive by to see the atmosphere, and ask people with similar taste preferences.

Create simple tracking systems for recurring decisions. If you’re trying to improve your sleep, track not just hours slept, but also caffeine intake, screen time before bed, room temperature, and stress levels. Patterns emerge when you look at multiple variables over time.

Diversify your sources actively. If you’re considering a career change, don’t just talk to people already in that field – they might have survivor bias. Seek out people who tried and left, recruiters who place candidates in those roles, and industry publications that discuss challenges and trends.

Analyze Results Objectively Without Emotional Bias

Emotions are data, but they’re not the only data. When your experiment doesn’t work out as hoped, your brain will try to protect your ego by finding excuses or dismissing the results. Scientists expect failure and learn from it.

Set success criteria before you start, not after you see the results. If you’re testing whether working from home improves your productivity, decide upfront what “improved productivity” means – completed tasks per day, quality ratings from your boss, or hours of focused work. This prevents you from moving the goalposts when results are mixed.

Look for contradicting evidence actively. If your hypothesis seems correct, challenge it by seeking information that might prove you wrong. This isn’t pessimism – it’s intellectual honesty. When you find flaws in your reasoning early, you save yourself from bigger mistakes later.

Keep emotion in its proper place by acknowledging it openly. “I really want this apartment to work out, so I might be overlooking red flags.” “I’m frustrated with my boss, which might be making me more critical of this project than I should be.” Once you name the emotional bias, you can work around it rather than being controlled by it.

Identify and Overcome Common Thinking Traps

Recognize Confirmation Bias in Your Information Consumption

Your brain loves being right. When you scroll through social media or read news articles, you naturally gravitate toward information that supports what you already believe. This mental shortcut, called confirmation bias, feels comfortable but creates dangerous blind spots in your thinking.

Watch how you consume information for a week. Do you only follow news sources that align with your political views? When researching a major purchase, do you focus on reviews that support the choice you’ve already made? Most people unconsciously seek out sources that validate their existing opinions while avoiding or dismissing contradictory evidence.

Breaking this pattern requires intentional effort. Start by diversifying your information diet. If you lean left politically, occasionally read center-right publications. If you’re considering buying a specific car model, actively search for negative reviews alongside positive ones. Create a habit of asking yourself: “What evidence would change my mind on this topic?”

Social media algorithms make confirmation bias worse by showing you content similar to what you’ve previously engaged with. Combat this by following accounts with different perspectives, using multiple search engines, and regularly clearing your browsing history to reset recommendation algorithms.

Avoid Hasty Generalizations from Limited Examples

Your friend got food poisoning at a restaurant, so you decide all restaurants in that chain are unsafe. Your coworker from Marketing is disorganized, so you assume everyone in Marketing lacks attention to detail. These snap judgments based on tiny sample sizes lead to faulty conclusions that can hurt relationships and limit opportunities.

Scientists understand that meaningful patterns emerge only from adequate sample sizes. One dramatic example doesn’t establish a trend, yet our brains treat vivid, memorable experiences as more significant than they actually are. A single plane crash gets more media attention than thousands of safe flights, making air travel seem more dangerous than driving despite statistics showing the opposite.

Before drawing broad conclusions, ask yourself: “How many examples am I basing this on?” If the answer is one or two, pump the brakes. Look for larger patterns over longer time periods. That terrible customer service experience might be an outlier, not representative of the company’s typical performance.

Practice collecting more data points before forming opinions. If you’re considering a new neighborhood, visit at different times and days rather than judging it based on one afternoon drive-through. When evaluating job candidates, use structured interviews and multiple touchpoints rather than relying on first impressions.

Question Correlation Versus Causation Assumptions

Ice cream sales spike during months when drowning incidents increase. Does ice cream cause drowning? Obviously not – both increase during summer when people swim more and eat more frozen treats. This silly example illustrates a serious thinking trap that fools even smart people: assuming correlation equals causation.

Two things happening together doesn’t mean one causes the other. They might both be caused by a third factor, occur by coincidence, or have a more complex relationship than simple cause-and-effect. Medical studies spend billions of dollars and years of research to establish whether treatments actually cause improvements or just correlate with them.

In daily life, you encounter these false connections constantly. Cities with more police officers have higher crime rates – not because police cause crime, but because crime-ridden cities hire more officers. Students who eat breakfast score higher on tests – not necessarily because breakfast boosts performance, but potentially because families that prioritize breakfast also emphasize education.

When you notice two things happening together, pause and consider alternative explanations. Could a third factor influence both? Might the relationship work in reverse? Could this be pure coincidence? This mental habit prevents costly mistakes like investing in stocks based on misleading patterns or making major life changes based on superficial connections.

Develop Evidence-Based Problem Solving Skills

Separate facts from opinions in complex situations

Facts remain true regardless of who states them, while opinions reflect personal beliefs and interpretations. When facing complex problems, smart thinkers learn to distinguish between these two. Start by looking for verifiable information: numbers, dates, documented events, and measurable outcomes. These represent your factual foundation.

Opinions often hide behind persuasive language. Watch for words like “should,” “best,” “terrible,” or “obviously” – these signal subjective judgments rather than objective reality. Someone might say “This marketing strategy is brilliant,” but the facts might show declining engagement rates and poor conversion numbers.

Create two columns when analyzing information: one for facts, another for interpretations. If you’re deciding whether to invest in a company, separate the concrete data (revenue growth, debt levels, market share) from opinions about future potential or management quality.

Evaluate source credibility and potential conflicts of interest

Not all sources deserve equal weight in your decision-making process. Strong sources demonstrate expertise in the relevant field, maintain transparency about their methods, and have a track record of accuracy. Academic researchers, industry professionals with direct experience, and established institutions typically offer more reliable information than anonymous bloggers or social media personalities.

Dig deeper into motivations behind information sources. A pharmaceutical company’s study about their own drug carries inherent bias, even if the research follows proper protocols. Financial advisors recommending specific investments might earn commissions from those products. Restaurant reviews from food critics differ significantly from those written by restaurant owners’ friends.

| Source Type | Credibility Indicators | Red Flags |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Research | Peer review, methodology disclosure, institutional affiliation | Conflicts of interest not disclosed, small sample sizes |

| News Media | Multiple independent sources, fact-checking processes, corrections policy | Single unnamed sources, sensationalized headlines |

| Expert Opinion | Relevant credentials, professional experience, balanced perspective | Financial incentives, extreme positions without evidence |

Always ask: Who benefits if I believe this information? What expertise does this source actually have? Are they sharing data or trying to sell something?

Use data to validate or challenge your initial assumptions

Your gut feelings might point you in the right direction, but data shows you whether you’re actually on the right path. Before making important decisions, identify your assumptions and find ways to test them with real information.

Say you assume your team works better in the office than remotely. Instead of acting on this feeling, measure productivity metrics, track project completion times, and survey team satisfaction levels for both work environments. The data might confirm your assumption – or completely flip your thinking.

Start small when gathering validation data. If you’re considering a career change, don’t quit your job immediately. Instead, take on freelance projects in your target field, informational interviews with professionals, or online courses to test your interest and aptitude. Track your engagement levels, skill development speed, and overall satisfaction throughout this process.

Test solutions on a small scale before full implementation

Smart problem-solving means reducing risk through experimentation. Rather than betting everything on one solution, run small-scale tests that give you valuable feedback without major consequences.

Restaurants test new menu items in a few locations before rolling them out company-wide. Software companies release beta versions to limited user groups before launching publicly. You can apply the same principle to personal and professional challenges.

Planning a major home renovation? Start with one room to test your contractor, timeline estimates, and budget projections. Considering a new morning routine? Try it for one week rather than committing to permanent changes. Want to switch careers? Take on part-time work or volunteer opportunities in your target field before making the full transition.

Create simple metrics to evaluate your small-scale tests: cost, time investment, stress levels, and desired outcomes. Document what works, what doesn’t, and what unexpected issues arise. This approach saves money, time, and frustration while building confidence in your larger decisions.

Apply Logical Reasoning to Personal Relationships

Analyze Communication Patterns Objectively

When tensions rise in relationships, we often get caught up in emotional reactions rather than stepping back to see what’s really happening. Start tracking communication patterns like a data scientist would track trends. Notice when arguments typically occur – is it when one person feels overwhelmed at work? Does criticism emerge when someone’s feeling insecure about something else entirely?

Create mental notes about the actual words being used versus the underlying emotions. Your partner might say “You never help with dishes” when they’re really expressing feeling unappreciated. Your friend could complain about your response time to texts when they’re actually feeling disconnected from you overall. By observing these patterns without immediately defending yourself, you gain valuable insights into what’s driving the real issues.

Keep a simple log for a week – write down the topic of disagreements, the time they happened, and what preceded them. You’ll start seeing patterns that emotion alone would never reveal. Maybe conflicts spike when someone’s hungry, tired, or dealing with external stress. This objective approach removes the personal sting and helps you address root causes instead of surface symptoms.

Test Assumptions About Others’ Motivations

We’re natural mind readers – or at least we think we are. When someone cancels plans last minute, we immediately assume they don’t value our time. When a colleague seems distant, we decide they must dislike us. These mental shortcuts save time but often lead us astray.

Start treating your assumptions like scientific hypotheses that need testing. Before concluding that your friend is being passive-aggressive, consider alternative explanations. Maybe they’re going through a tough time, dealing with family issues, or simply having an off day. The key is generating multiple possible explanations rather than settling on the first one that comes to mind.

Practice the “generous assumption” experiment. For one week, when someone behaves in a way that bothers you, deliberately choose the most generous interpretation of their actions. Your teenager’s eye-rolling might come from feeling overwhelmed rather than disrespecting you. Your spouse’s quietness could signal exhaustion rather than anger. Track how often your generous assumptions prove more accurate than your initial negative ones.

Ask direct questions when appropriate: “I noticed you seemed quiet during dinner – everything okay?” This simple approach often reveals that your assumptions were completely wrong and saves relationships from unnecessary strain.

Base Decisions on Observable Behaviors Rather Than Speculation

Relationship decisions based on speculation create problems that don’t actually exist. Instead of wondering if someone cares about you, look at their actions. Do they remember important things you’ve told them? Do they make time for you when you need support? Do their behaviors match their words consistently over time?

Create a simple framework for evaluating relationships based on observable evidence:

Green Flags (Consistent Behaviors):

- Follows through on commitments

- Communicates openly about problems

- Shows up during difficult times

- Respects your boundaries

- Makes effort to understand your perspective

Red Flags (Consistent Patterns):

- Says one thing, does another

- Blames you for their emotional reactions

- Dismisses your concerns without discussion

- Violates agreed-upon boundaries repeatedly

- Only contacts you when they need something

Focus on patterns over isolated incidents. Everyone has bad days, but consistent behavior patterns reveal true character and intentions. When making important relationship decisions – whether to move in together, end a friendship, or set new boundaries – base these choices on documented behaviors rather than hopes, promises, or potential you imagine someone might have.

Stop trying to decode mixed signals. When someone’s actions don’t match their words, believe the actions. This evidence-based approach protects you from wasting energy on relationships that aren’t actually working while helping you recognize and invest in the ones that truly are.

Make Smarter Financial and Career Choices

Research Market Trends Using Reliable Data Sources

Smart financial decisions start with solid information. Skip the flashy headlines and social media tips that promise quick riches. Instead, build your research foundation on government databases like the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Reserve Economic Data, and SEC filings. These sources provide raw numbers without the marketing spin.

Look for patterns over multiple years rather than reacting to monthly fluctuations. Housing markets, for example, show clearer trends when you examine 5-10 year cycles instead of last quarter’s changes. Use multiple data points to cross-verify your findings – if unemployment rates are dropping but wages remain flat, that tells a different story than rising employment with corresponding salary growth.

Create your own tracking system for the metrics that matter to your situation. Whether you’re monitoring rental prices in your target neighborhood or tracking industry salary ranges for your field, consistent data collection beats sporadic research every time.

Test Investment Strategies with Small Amounts First

Before committing serious money to any investment approach, run small-scale experiments. Start with amounts you can afford to lose completely – think $100-500 rather than thousands. This practice lets you experience the emotional reality of watching your money fluctuate without risking your financial security.

Track both the numbers and your feelings during these test runs. Did you panic when your investment dropped 15%? Did you get overconfident after a quick gain and want to invest more immediately? These emotional responses reveal crucial information about your risk tolerance that no online quiz can measure.

Document what works and what doesn’t. Maybe dollar-cost averaging into index funds feels manageable, but picking individual stocks keeps you awake at night. Perhaps you handle real estate crowdfunding platforms better than cryptocurrency volatility. Your pilot tests become a personal guidebook for larger investment decisions.

Evaluate Job Opportunities Using Measurable Criteria

Create a scoring system for job opportunities that goes beyond gut feelings. List the factors that actually matter for your career goals – salary range, learning opportunities, work-life balance, company growth trajectory, and advancement potential. Assign weights to each factor based on your current priorities.

Research companies thoroughly using employee review sites, financial reports, and industry publications. Look for concrete metrics: employee turnover rates, revenue growth, market position, and recent news coverage. A company with declining revenues might offer lower job security, regardless of how impressive the office looks during your interview.

Compare offers using your predetermined criteria rather than making decisions in the moment. That exciting startup might score high on learning opportunities but low on financial stability. The established corporation could offer better benefits but limited growth potential. Your scoring system helps you see trade-offs clearly instead of getting swept up in interview excitement.

Question Emotional Spending Triggers Through Systematic Observation

Track your spending patterns alongside your emotional states for at least one month. Note what you were feeling right before making purchases – stressed, bored, celebrating, or trying to impress someone. This data reveals your personal spending triggers more accurately than general advice about avoiding impulse purchases.

Set up friction barriers for emotional spending. Wait 24 hours before buying anything over a certain amount. Keep a running list of items you want but don’t need immediately. Many of these “must-have” purchases lose their appeal after a cooling-off period.

Analyze your environment’s influence on spending decisions. Do you overspend when shopping with certain friends? Does browsing social media lead to online purchases? Are you more likely to buy expensive items when you’re tired or hungry? Understanding these patterns helps you make conscious choices about when and where to make spending decisions.

The scientific method isn’t just for labs and research papers—it’s your secret weapon for navigating daily life with clarity and confidence. When you start questioning assumptions, gathering evidence before jumping to conclusions, and testing your ideas against reality, you’ll find yourself making better decisions across the board. From spotting misleading information online to resolving conflicts with friends and family, these critical thinking skills help you cut through the noise and focus on what really matters.

Start small by questioning one assumption you make today, whether it’s about a news headline, a relationship issue, or a financial decision. Practice gathering facts before forming opinions, and don’t be afraid to change your mind when new evidence shows up. Your future self will thank you for developing these thinking habits—they’re the difference between reacting to life and actively shaping it with smart, informed choices.